Europe’s 1995 Ryder Cup victory: expect the unexpected

Europe’s 1995 Ryder Cup victory: A remarkable tale of the unexpected

Subscribe to the Golf Monthly newsletter to stay up to date with all the latest tour news, equipment news, reviews, head-to-heads and buyer’s guides from our team of experienced experts.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for all the latest tour news, gear reviews, head-to-heads and buyer’s guides plus features, tips from our top 50 coaches and rules advice from our expert team.

Once a week

Kick Point

Sign up to our free Kick Point newsletter, filled with the latest gear reviews and expert advice as well as the best deals we spot each week.

Once a week

Women's Golf Edit

Sign up to our free newsletter, filled with news, features, tips and best buys surrounding the world of women’s golf. If you’re a female golfer, you won’t want to miss out!

Having lost twice as captain, Bernard Gallacher took the helm once again in 1995, skippering an unfancied European side against a well-prepared American team at Oak Hill in New York State

Europe’s 1995 Ryder Cup victory: A remarkable tale of the unexpected

In the opening singles of the 1979 Ryder Cup at The Greenbrier, the Americans sent out Lanny Wadkins.

He’d won four of four to that stage and had been undefeated in the 1977 matches. The general consensus was a nailedon point for the home side. Scotland’s Bernard Gallacher had other ideas and outplayed Wadkins to win by 3&2.

In 1995 Gallacher faced his old pal Wadkins again, this time as opposing captains. The prognosis was similar to their individual encounter: Wadkins was sure to emerge victorious. But, once again, Gallacher hadn’t read the script.

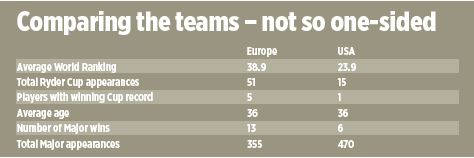

After narrow US victories at Kiawah Island in 1991 and The Belfry in 1993, the American media had returned to doom mongering about the future of the contest in the run-up to the 1995 matches at Oak Hill. Despite ten years of even contests, the American press felt it could only go one way. “The possibility of a rout looms large,” wrote Sports Illustrated. There was solid reasoning behind the prediction.

Firstly, the European side looked decidedly sketchy – Europe’s Ryder Cup talisman Seve Ballesteros was in poor form and struggling with a bad back, Bernhard Langer also had back trouble, Nick Faldo had injured his wrist and Jose Maria Olazabal had withdrawn because of foot problems. Ian Woosnam had required a captain’s pick after a midseason slump and the remainder of the team comprised a rag-tag assortment of players the US press had little knowledge of.

Subscribe to the Golf Monthly newsletter to stay up to date with all the latest tour news, equipment news, reviews, head-to-heads and buyer’s guides from our team of experienced experts.

David Gilford had played before in 1991, but he lost two matches before being dropped for the singles when Steve Pate was injured. His inclusion didn’t have the Americans quaking in their boots. Also falling a little shy in the intimidation stakes were Ireland’s Philip Walton – a rookie who’d missed the cut in six of the ten Majors he’d played – and Per-Ulrik Johansson, another rookie with just two European Tour wins. Mark James, Howard Clark and Sam Torrance were over 40 and Constantino Rocca was only just behind. The only player the Americans couldn’t fault was Colin Montgomerie. He’d been runner-up in the 1994 US Open and had just finished second to Steve Elkington in the USPGA.

A testing set-up

Another reason for scepticism about Europe’s chances was the course at Oak Hill. A testing Donald Ross design with ten par 4s measuring over 400 yards, it had been used for three US Opens, and Wadkins wanted the track set up in US Open style: knee-high rough, narrow fairways and firm greens.

It was an obvious tactic as no player on the European side, save Monty and Faldo, had finished better than a tie for 18th in the US Open since 1988. By contrast, the US side contained the current US Open champion Corey Pavin, Tom Lehman – third behind Pavin at Shinnecock Hills, Jeff Maggert and Phil Mickelson – both tied fourth in that event, Jay Haas, Davis Love III, Loren Roberts, who’d lost a play-off for the 1994 US Open, two-time US Open winner Curtis Strange, two-time 1995 PGA Tour winner Peter Jacobsen, putting god Brad Faxon and former Masters winners Fred Couples and Ben Crenshaw. Taking these factors into consideration, the pre-match analysis in Sports Illustrated seemed justified. The Europeans had no chance.

The first day foursomes kicked off with a barnstorming match: Pavin and Lehman versus Faldo and Montgomerie. The tone was set when Faldo berated Lehman for holing out a short putt on the 2nd green for a win. Apparently Lehman hadn’t heard Faldo concede. “When I say it’s good, it’s good!” Faldo shouted across the green.

After some brilliance and exceptional scrapping, Europe’s best pairing came up just shy. It didn’t bode well.

Few expected Torrance and Rocca to fare any better against Haas and Couples. Rocca had never played alternate shots and Torrance had lost seven of eight previous foursomes. But the Europeans battled to win by 3&2.

Veterans Clark and James were brushed aside by Love III and Maggert, but Johansson and Langer insured the soggy session was tied as they came through a tough match against Crenshaw and Strange.

Captain Gallacher could feel content with Europe’s performance at 2-2. The fourballs were to prove more challenging.

In the opening match, Seve got his first outing, paired with quiet Englishman David Gilford. The Spaniard, full of passion but not on his game, could do little but provide encouragement. “You’re the best player out here today,” Seve kept saying, putting his arm around the Englishman. Gilford responded and Europe won 4&3.

But that was the only glimmer in the session for Gallacher’s men. The remaining three pairings lost, including a second defeat for Faldo and Monty. Europe ended the day 5-3 down and there seemed a gulf in class. The American press had little cause to question their pre-match confidence.

But the Europeans weren’t beaten and they came out firing in the Saturday foursomes. Faldo and Monty finally put a point on the board, Torrance and Rocca delivered a thumping 6&5 victory and Gilford secured another point. He and Langer beat the strong pairing of Lehman and Pavin. It was 6-6 and the European tail was up. It was to droop once again in the fourballs.

Monty and Torrance fell to Faxon and Couples. Seve continued to play desperately badly and this time was unable to inspire Gilford against Haas and Mickelson. Langer and Faldo narrowly lost to Pavin and Roberts.

The only afternoon point came courtesy of the diminutive pairing of Woosnam and Rocca who coasted past Love III and Crenshaw.

In need of inspiration

So it was 9-7 to the USA going into the final round and, just as after the first day, the outcome looked inevitable. The Americans would prove their superiority in the singles as they had done so often before. In the history of the Ryder Cup, only four teams had ever come back to win taking a deficit into the singles. If Europe were to do it they’d need to play outstandingly, and captain Gallacher would need to employ shrewd tactics.

Leading with Seve was a perfect move. Gallacher knew the Spaniard was unlikely to win playing as he was. The European skipper reckoned on Wadkins sending a strong player out first. If Seve went up against one of their best he would lose, but it would mean another European might face less-challenging opposition. It worked. Wadkins led with Lehman, who beat Ballesteros easily by 4&3. The Americans had wasted a trump card.

Next, Gallacher chose experience. Clark at two and James at three could draw on five and six previous Ryder Cups respectively. Clark beat Jacobsen, helped by a hole-in-one on the 11th, and James saw off Maggert.

Gallacher put some of his strongest players at either end of the middle order. Woosnam went up against Couples for the second straight Ryder Cup and the result was the same – a fighting half. After Love III had seen off Rocca, the score was 11.5-9.5 to the USA. The predicted result still seemed likely.

But Monty fought back by seeing off Crenshaw 3&1. Then the heroics really started.

In his match with Faxon, Gilford went to the last 1 up. This would be a crucial point and Gilford knew it. His approach to the final hole displayed the tension landing long and left. He duffed his chip and was still not on the green, while Faxon blasted out of a greenside bunker leaving a testing downhiller for par. Gilford chipped on, holed a ten-foot putt for a five and watched as one of the world’s best putters faced a seven-footer to half the match. As his ball drifted past the right edge, Faxon closed his eyes in agony. It was 11.5-11.5.

Langer lost to Pavin but Torrance beat Roberts to keep things level. The pressure was on Faldo as he battled to come back againstStrange. After holing a superb winning putton the 17th, the Englishman was all-square.

Nerves were clearly a factor on the last as Faldo drove into thick rough, requiring a hack back to shorter grass. Strange struck a poor second that snagged in the long rough short of the green. Faldo then played an incredible pitch that ended four feet from the hole and Strange did well to get his chip to within six feet, but his putt lipped out. Faldo holed his for the win. Strange had bogeyed the last three to lose by one. A tearful Seve embraced Faldo: Europe needed just one more point.

It fell to the unlikeliest of players to deliver it. Philip Walton, playing against Jay Haas, was 3 up with three to play and looked to be cruising. But Haas holed a bunker shot to win the 16th and then claimed the 17th.

Team USA was still alive, but clinging on by its fingernails. Haas had to win the last. His tee shot made the job difficult, an ugly hook into the trees. Walton’s tee shot wasn’t much better, into the right hand rough. But he did at least have a shot at reaching the green in two. Blasting a 5-wood, he nearly made it, finding the thick rough just short. Haas’ third spun back to the front of the green and, when Walton somehow managed to creep his pitch up to within ten feet of the hole, Haas had to hole or Walton would have two for it. The American did miss, so Walton stood up with two putts for the Ryder Cup. He was so nervous he could barely take the putter away from the ball.

“My legs felt like they belonged to someone else,” he said. But he tickled his putt down to within a foot of the hole. Haas conceded and the Cup was Europe’s. Bernard Gallacher ran on to the green and lifted an emotional Walton into the air. On his 11th attempt (eight as a player, three as captain), this was the first time Gallacher had been part of a winning Ryder Cup team.

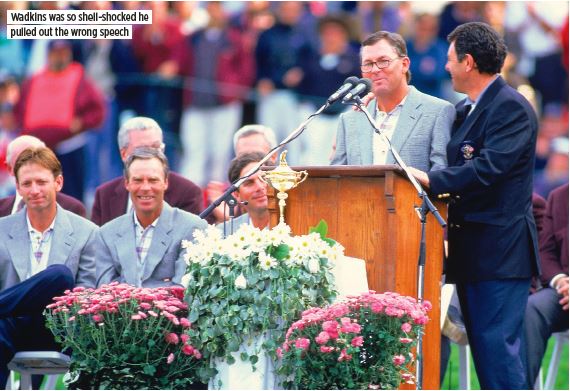

Gallacher was elated at the comeback; Wadkins was so shell-shocked that he could barely speak at the closing ceremony. He was in such disbelief he accidentally pulled the wrong speech from his pocket – the one he’d written to accept victory. It was automatic pilot; it had looked a foregone conclusion.

Europe had defied all reasonable logic to win by the narrowest of margins. An ageing, injured, off-form and inexperienced team had beaten a side of high-ranking Americans on their turf over a course set up to suit their games. The 1995 Ryder Cup encapsulated what makes the event so consistently exciting – the very real possibility of the unexpected.

Fergus is Golf Monthly's resident expert on the history of the game and has written extensively on that subject. He has also worked with Golf Monthly to produce a podcast series. Called 18 Majors: The Golf History Show it offers new and in-depth perspectives on some of the most important moments in golf's long history. You can find all the details about it here.

He is a golf obsessive and 1-handicapper. Growing up in the North East of Scotland, golf runs through his veins and his passion for the sport was bolstered during his time at St Andrews university studying history. He went on to earn a post graduate diploma from the London School of Journalism. Fergus has worked for Golf Monthly since 2004 and has written two books on the game; "Great Golf Debates" together with Jezz Ellwood of Golf Monthly and the history section of "The Ultimate Golf Book" together with Neil Tappin , also of Golf Monthly.

Fergus once shanked a ball from just over Granny Clark's Wynd on the 18th of the Old Course that struck the St Andrews Golf Club and rebounded into the Valley of Sin, from where he saved par. Who says there's no golfing god?