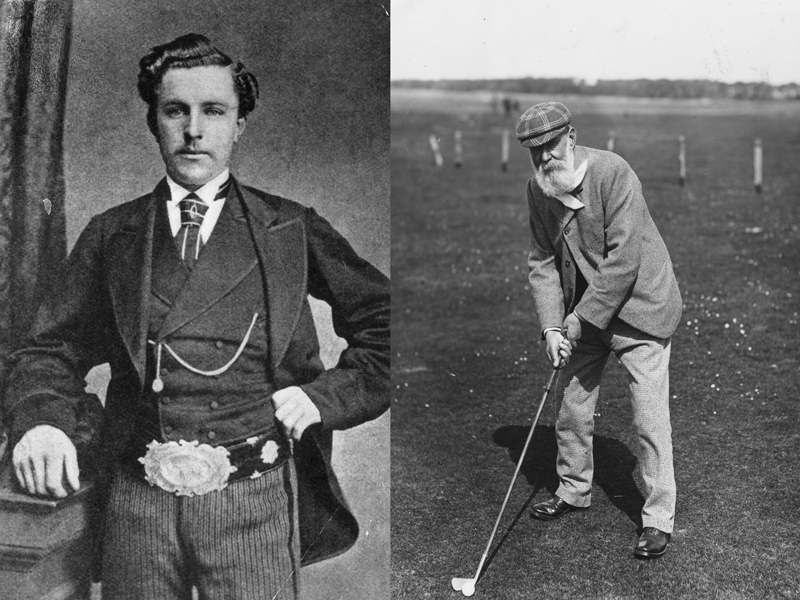

Golf’s Founding Father and Son

The story of Old and Young Tom Morris is one of triumph and tragedy

Subscribe to the Golf Monthly newsletter to stay up to date with all the latest tour news, equipment news, reviews, head-to-heads and buyer’s guides from our team of experienced experts.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The story of Old and Young Tom Morris of St Andrews, two of the most iconic figures in golf's early history, Their tale is one of triumph and tragedy.

In September 1878, the Lord Justice General of Scotland John Inglis unveiled a monument against the south wall of the graveyard at St Andrews Cathedral. Commissioned by 60 golf societies from England and Scotland, it depicted a young golfer in tweeds and Balmoral bonnet addressing a ball. The inscription on it read, “In memory of ‘Tommy,’ son of Thomas Morris. Deeply regretted by numerous friends and golfers, he thrice in succession won the Championship Belt and held it without envy, his many amiable qualities being no less acknowledged than his golfing achievements.”

Young Tom Morris died on Christmas Day in 1875 aged just 24. The official cause of death was a pulmonary haemorrhage though, as his wife Margaret and newborn son had tragically died in childbirth three months earlier, many speculated he succumbed to a broken heart. “If that were true, I wouldn’t be here either,” said his grief-stricken father.

Between them Old and Young Tom Morris won eight of the first 12 Open Championships and set countless records, many still standing. The pair were idolised in Scotland and beyond and their names will forever be associated with the emergence of golf as a professional sport.

Tom Morris was born in St Andrews in 1821, the same year James Cheape of Strathtyrum purchased the links there for the golfers to prevent rabbit farmers taking over. Golf already flowed through the veins of the historic town. Old Tom once said of the St Andreans, “We were all born with webbed feet and a golf club in our hand.”

Tom began his golfing career hitting corks weighted with nails around the streets of the town in a game the local youngsters called “sillybodkins.”

After finishing school at the age of 14, Tom’s father arranged a meeting for him with the ball-maker and caddy Allan Robertson. Tom was taken on as an apprentice and Robertson taught him to make a “feathery” and also how to play the game of golf on the links.

Subscribe to the Golf Monthly newsletter to stay up to date with all the latest tour news, equipment news, reviews, head-to-heads and buyer’s guides from our team of experienced experts.

He spent four years as an apprentice then became a journeyman, making balls for Robertson, caddying, playing matches and all the while improving at the game. By 1842 he was a rival to his supposedly unbeatable mentor.

The pair won a series of foursomes matches together and were good friends until a seemingly innocuous incident changed things forever.

Playing with a Royal and Ancient member John Campbell, Tom ran out of balls on the inward nine and John lent him a rubber “gutty.” A new invention made of “gutta percha,” it was more durable and cheaper than the feathery. Robertson was dismayed at the arrival of the gutty as it threatened his livelihood.

As John and Tom neared the home holes, they passed Robertson heading out. Robertson spied his protégé playing the gutty and, as Tom later put it, “In such a temper cried out to me never to show face again.” And that was that.

In 1851 Tom moved his wife Nancy and their baby son Tommy to Prestwick where Tom had accepted a job as “Keeper of the Green.” He designed and laid out a 12-hole course over the links there, completing much of the construction work himself. Later Tom would be recognised as one of the first great course architects, he designed numerous layouts including Muirfield, Moray, Lahinch and Westward Ho!

At Prestwick, Tom gave instruction to the members, mended clubs and earned good money by making Allan Robertson’s hated gutties.

In 1860, a year after Robertson’s untimely death, Lord Eglinton and Colonel James Ogilvie Fairlie decided to host a professional tournament to raise Prestwick’s standing as a club. A Championship Belt would be on offer to the victor.

It wasn’t Tom as expected, however, who came out on top in that first Open Championship. Willie Park of Musselburgh tied Tom over 36 holes then went on to beat him in a playoff. Nine-year-old Tommy watched in disbelief as his dad was defeated.

As a player Tom was highly skilled, though not infallible. In his early matches with Allan Robertson he developed a reputation for fragility from close range. An R&A member once sent Tom a postcard addressed simply to, “The Misser of Short Putts, Prestwick.” The postman was in no doubt of the intended recipient.

But Tom had a slow, smooth and consistent swing, a cool temperament and a fiercely competitive nature. When the Open was contested a second time at Prestwick in 1861, Tom defeated Park by four. In 1862 he beat his rival by an astonishing 13 strokes, a winning margin that’s never been equalled.

Tom took the belt for a third time in 1864 then moved his family back to St Andrews that December after accepting a job as custodian of the links for the R&A – a post he would hold until his retirement in 1904.

By the time of their return to St Andrews, young Tommy had already begun to show his skill as a golfer. In 1864, at the age of just 13, he won a match in Perth against a local prodigy and picked up a prize of 15 pounds. A newspaper report read, “Master Morris seems to have been both born and bred to golf.”

In 1867 Tommy won a professional event at Carnoustie and travelled to that year’s Open at Prestwick amongst the favourites. But the 16-year-old failed to fire on all cylinders and it was once again left to his, then 46-year-old, father and Willie Park to fight it out for the belt. Old Tom prevailed and secured his final Open victory – he remains the oldest winner of the great event.

The following year his son would become the youngest ever winner.

Tommy was tall and strong for his age, able to hit the ball prodigious distances with a low, penetrating ball flight. He played with style and finesse and had a natural touch around the greens. He developed a shot with his rutting iron (equivalent to a modern sand wedge,) hitting firmly down on the back of the ball and generating backspin – previously unheard of.

When the Open returned to Prestwick in 1868, Young Tommy lived up to his potential. He set two course records en-route to victory over his father. The Championship belt once again belonged to a Morris.

Young Tommy looked unstoppable and he proved it the following year, retaining his title. In 1870 he had the chance to become the first man to win the Championship three years straight, and keep the belt in so doing. He managed it with something to spare, beating Davie Strath by 12 shots. His first round of 47 (Prestwick was then a 12-hole course) included an incredible eagle three at the 578 yard first.

There was no Open in 1871, but in 1872 Tommy won again and his was the first name inscribed on the new trophy – a silver Claret Jug. He remains the only man to win four straight Championships.

Amazingly, neither Morris ever won the Open in their hometown. Old Tom was past his prime when the Championship was first contested at St Andrews in 1873. Young Tom fell just short that year, finished second at Musselburgh in 1874 and didn’t play another Open.

In November of 1874, Tommy married Margaret (Meg) Drinnen from Edinburgh. The pair settled happily into a house on Playfair Place in St Andrews and Meg was soon pregnant.

In September of 1875 Old Tom, now 54, agreed to a £25 match between he and Tommy and the Park brothers (Willie and Mungo) at North Berwick. Tommy was reluctant to go as Meg was nearing her due date, but he needed the money and eventually agreed.

Over a four-round contest, the St Andrews men were triumphant on the final green, but celebrations were short-lived. During the last round, Old Tom had intercepted a telegram for Tommy telling him to return home “post-haste” as Meg was ill. Tom didn’t reveal the information until the final putt had dropped.

Father and son found a sail boat to take them back across the Firth but, by the time they reached St Andrews harbour, a messenger stood there with news both mother and child were dead. Before the year was out, so was father.

After his son’s death, a subdued Tom carried on in his role as custodian of the green for the R&A but cut back on his money-matches. He contested 19 more Open Championships and played his last in 1895 at the age of 74.

Tom continued to tread the links into his 80s, partnering local worthies and visiting dignitaries. He was St Andrews’ most famous figure and had earned the nickname, “Grand Old Man.” In 1902 the R&A commissioned George Reid to paint his portrait, a work that still hangs proudly in the clubhouse.

In 1908 Old Tom, having outlived his wife and children, died after falling down the stairs at St Andrews’ New Golf Club. His funeral parade stretched the length of South Street from the Westport to the Cathedral.

140 and 107 years after their deaths, the Morrises remain two of golf’s most iconic figures – The father for his longevity as the game’s Grand Old Man, the son as a flamboyant talent, tragically cut down in his prime.

QUOTES

“I could cope with them all on the course. All but Tommy. He was the best the old game ever saw.” Old Tom Morris

“ He was always cheerful during a life which met with almost continual disappointments and sorrows.” Writer John L. Low on Old Tom

“It was probable that Tommy attained a rare pitch of excellence at as early an age as any golfer on record.” H.S.C. Everard

“He has been written of as often as a Prime Minister, been photographed as often as professional beauty, and yet remains, through all the advertisement, exactly the same, simple and kindly.” Writer Horace Hutchinson on Old Tom

Fergus is Golf Monthly's resident expert on the history of the game and has written extensively on that subject. He has also worked with Golf Monthly to produce a podcast series. Called 18 Majors: The Golf History Show it offers new and in-depth perspectives on some of the most important moments in golf's long history. You can find all the details about it here.

He is a golf obsessive and 1-handicapper. Growing up in the North East of Scotland, golf runs through his veins and his passion for the sport was bolstered during his time at St Andrews university studying history. He went on to earn a post graduate diploma from the London School of Journalism. Fergus has worked for Golf Monthly since 2004 and has written two books on the game; "Great Golf Debates" together with Jezz Ellwood of Golf Monthly and the history section of "The Ultimate Golf Book" together with Neil Tappin , also of Golf Monthly.

Fergus once shanked a ball from just over Granny Clark's Wynd on the 18th of the Old Course that struck the St Andrews Golf Club and rebounded into the Valley of Sin, from where he saved par. Who says there's no golfing god?