Nick Faldo and David Leadbetter – The Great Swing Rebuild

The swing rebuild – Alex Narey looks back on how Nick Faldo became the world’s greatest player after hooking up with coach David Leadbetter

Subscribe to the Golf Monthly newsletter to stay up to date with all the latest tour news, equipment news, reviews, head-to-heads and buyer’s guides from our team of experienced experts.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

After Rory McIlroy’s split from coach Pete Cowen, questions continue to loom over whether the Northern Irishman will ever recapture the form that made him, without question, the world’s best player.

Searching for perfection in a bid to regain the technique that made him so untouchable on the golf course, McIlroy’s decision to work solely with long-time coach Michael Bannon after an eight-month stint with Cowen looks something of a puzzling move.

Despite a drop down the rankings, Cowen, after all, oversaw two PGA Tour victories with McIlroy. Hardly the worst return.

The move brings to light the importance of the swing coach: they are more than simply a guiding hand on the range, but a sounding board for advice and complete reassurance.

That is perhaps what McIlroy sees in Bannon that he did not in Cowen. Technically and emotionally, the relationship has to be spot on.

Patience is the key...

Many successful partnerships only require simple tweaks. Rarely are complete overhauls and rebuilds successful or even common.

Top-level sport affords no time for that because somebody else will take your place.

Subscribe to the Golf Monthly newsletter to stay up to date with all the latest tour news, equipment news, reviews, head-to-heads and buyer’s guides from our team of experienced experts.

But 37 years ago, one golfer realised it was his only option.

Sun City, South Africa, December 1984, and Nick Faldo first crosses paths with David Leadbetter.

Faldo, 27 at the time, was a multiple winner on both the PGA and European Tours, and a year earlier had won the latter’s Order of Merit with a staggering return of five wins.

He’d already played in four Ryder Cups, making his first appearance at the age of 20 just six years after taking the game up. A natural talent, he was considered something of a phenom.

But inside, there were doubts. Faldo knew his game needed something else to stand up to the rigours of winning the game’s biggest prizes.

“You haven’t got it,” he would tell himself. Drastic action was required.

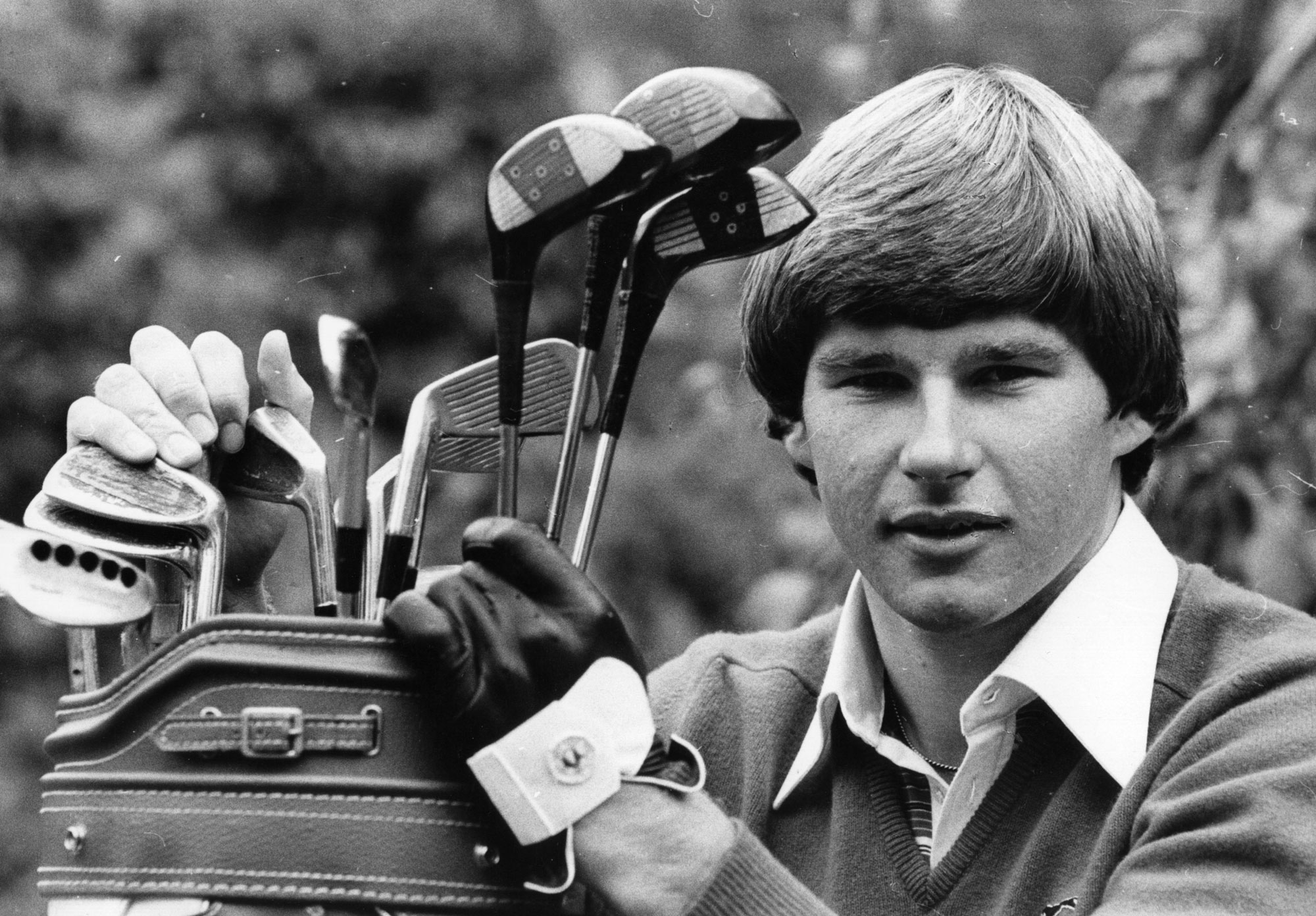

Nick Faldo in 1978

New direction

Leadbetter, at that time, was relatively unknown in coaching circles following a modest career as a player, but was building a reputation as a teacher with a sharp focus on the mechanics of the golf swing and had enjoyed success guiding a young and promising Zimbabwean named Nick Price.

That chance meeting between Faldo and Leadbetter in South Africa was brief, but it opened the player’s mind to the surgery that was needed and midway through 1985, as his form continued to dip, the partnership became more formal.

In an interview with Open.com earlier this year, Leadbetter said: “You have to remember he’d been pretty successful up to that point anyway. He’d won in America and the Order of Merit, so was a star player.

“When we first sat down and chatted, he said he wasn’t satisfied and felt he was only using about 75 per cent of what he had. It was a leap of faith, no question about it.”

Leadbetter noted that Faldo’s swing was too steep and wanted to get a better connection between the body and arms.

The pair targeted a rebuild in segments, starting with the rotation of the arms.

Driven

Faldo worked relentlessly in the Florida sun at Leadbetter’s teaching base, hitting thousands of balls on the range as they moved through the mechanics.

There was rarely a target. It was just ball after ball after ball.

And yet, on the course, things went from bad to worse.

Winless in 1985, Faldo could only watch haplessly as two of his European contemporaries, Bernhard Langer and Sandy Lyle, won their first Majors at the Masters and Open respectively.

Indeed, in his autobiography, Life Swings, Faldo admits to being ‘green with envy’ that Lyle had become the first British winner of the Claret Jug since Tony Jacklin. A somewhat bitter rivalry and clash of personalities between the pair only added to Faldo’s pain as his game continued to desert him.

Faldo and Leadbetter continued to graft – their aim was clear in what both saw as a two-year project: wholesale changes were needed if Faldo was to win a Major. Nothing else would do. Forget results, focus on the objective.

Others were not so patient, with a number of sponsors dropping the player as the weekly grind failed to materialise into tournament performances.

A rare high point came at the 1986 Open with Faldo registering a fifth-place finish. But he hadn’t played in the Masters or US Open that year and would miss the cut at the PGA Championship.

It was a woeful year.

Turning the corner

Then, in 1987 during Masters week, something clicked.

Faldo had not qualified to play at Augusta, and instead was competing in a satellite event at the Magnolia State Classic in Mississippi.

He finished second in that tournament, and Leadbetter had seen real progress.

“All the work he had put in over the previous two years was really coming to the fore,” said Leadbetter.

“That was the start of Nick’s climb. He owned his technique then, whereas up to that point he was just borrowing it. He was very comfortable with all the swing changes.”

Buoyed by an uplift in form, Faldo would eventually return to the winner’s circle five weeks later, claiming the Spanish Open by two strokes from Seve Ballesteros and Hugh Baiocchi.

Finally, he was up and running and by the time of the 1987 Open at Muirfield, he had edged his way into the world’s top 50.

“We had done everything geared to winning the Open,” said Leadbetter, who still marvels at Faldo’s performance over those four days 34 years ago as the wind and mist swept in off the East Lothian coast.

Winning that Open proved the ultimate examination. Proof that a swing built for longevity would be able to stand up to the game’s toughest test.

In the same way that Faldo had adopted his new swing changes, he remained patient and never panicked, even during the final round as he slipped three shots adrift of leader Paul Azinger at the turn.

But the American wilted, and Faldo remained metronomic. Eighteen consecutive pars were enough to seal a one-shot victory as Azinger bunkered on the last and failed to get up and down.

Leadbetter said: “I have never had anybody so single-minded. He had that goal in mind to be the player that he knew he could be.

“I’ve obviously had players with tremendous talent and players who certainly have desire and goals, but he was just something else.”

The relationship continued for another 11 years before the pair split, in somewhat sticky circumstances, in 1998.

Now 41, and with a wave of fresh talent threatening in the Majors, the player was not the same force but in many ways this story had reached its natural end: Six Majors had been won making Faldo the most dominant player of his era.

Writing of their break-up in Life Swings – that came after Leadbetter had failed to attend the 1998 PGA despite an apparent slump in his player’s form – Faldo said: “We never became close but I am disappointed in the nature of our parting.

“Nevertheless, it was an incredible 13-year partnership. We both honed our skills.

“And boy did we graft to get it done. As our careers have developed over the years I would genuinely regard David’s techniques as ground-breaking.”

Nick Faldo celebrates winning the 1987 Open

Alex began his journalism career in regional newspapers in 2001 and moved to the Press Association four years later. He spent three years working at Dennis Publishing before first joining Golf Monthly, where he was on the staff from 2008 to 2015 as the brand's managing editor, overseeing the day-to-day running of our award-winning magazine while also contributing across various digital platforms. A specialist in news and feature content, he has interviewed many of the world's top golfers and returns to Golf Monthly after a three-year stint working on the Daily Telegraph's sports desk. His current role is diverse as he undertakes a number of duties, from managing creative solutions campaigns in both digital and print to writing long-form features for the magazine. Alex has enjoyed a life-long passion for golf and currently plays to a handicap of 13 at Tylney Park Golf Club in Hampshire.